Finn and the Bell

Finn Rooney killed himself on January 3, 2020 in the afternoon after school. No one predicted it. There were no signs. All that can be said for sure is that there was a flash of high emotion that comes with youth, and there was a gun nearby, and bullets.

This isn't a story about suicide. It's a story about a boy called Finn who loved to fish and play baseball and write poetry and embroider...and what happens to a small Vermont community as it staggers forward after an unspeakable tragedy.

Make comment at bottom of this page. Because we really want to hear from you. And we want you to be able to hear from each other.

Here is a followup interview with Finn’s mom, Tara, in 2024

An interview with Rob Rosenthal for How Sound, on the making of Finn and the Bell

Thanks

My thanks to Tara Reese for her insights, her candor and her time. Thanks to my friends Amelia Meath, Tobin Anderson, Clare Dolan and Mark Davis for their help on this show. I also want to thank every single person who talked with me for this show. You didn't really want to but you did anyway. Thank you to Arron and Alleigh and Butch and David and Illia and Mike and Kim and Mirko and Alex and Mac and Allison and Dave and Jack and Dante and Bob and Ben and the Bread and Puppet Band.

Transcript

There is a transcript of the program at the bottom of this page.

RUMBLE STRIP: FINN AND THE BELL FINAL TRANSCRIPT (thanks to Russell Gragg and Radiolab for creating transcript)

RUMBLE STRIP: FINN AND THE BELL FINAL WEB TRANSCRIPT

(original broadcast 08-25-2023)

ERICA HEILMAN: Welcome to Rumble Strip. I'm Erica Heilman. Fair warning: this story involves suicide.

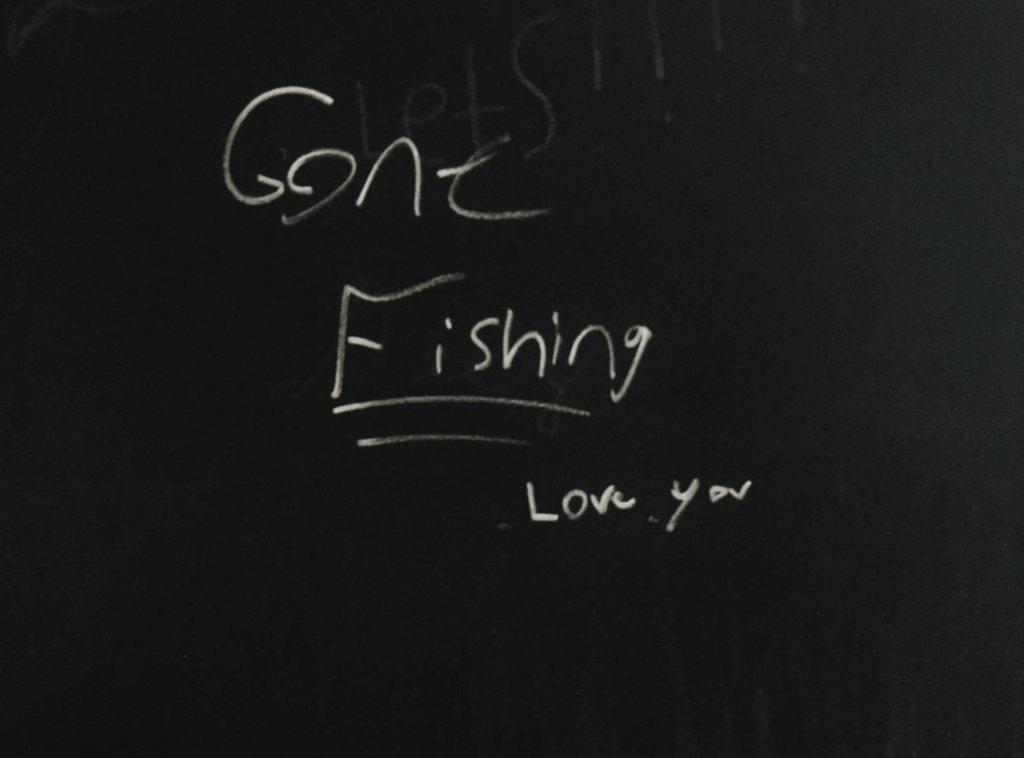

TARA REESE: He'd write little notes to find in weird places. You know, he'd write notes on—on logs, so when we would, you know, in the winter, deep in the winter go out to get wood for the fire, there'd be like a "Hi, Mama! I love you."

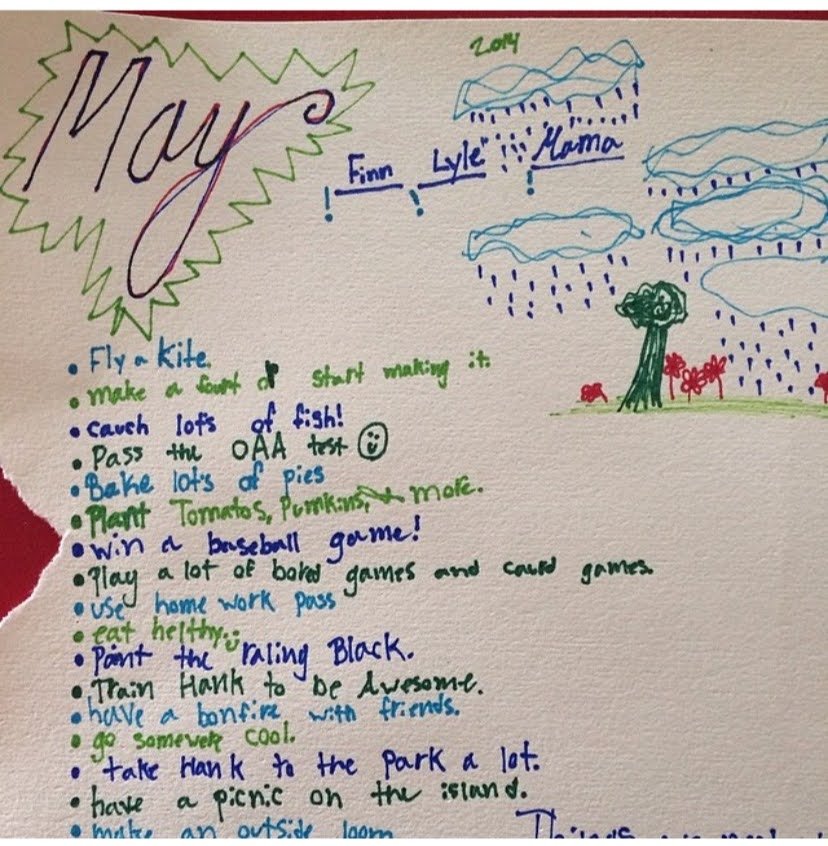

TARA REESE: I found one of them this summer. I was afraid I was going to, but also really wanted to. I couldn't decide which way I wanted to go with that. [laughs] He just recognized coziness, and was always trying to—to create that. What the blanket felt like was important, or like, "Let's get our pajamas on!" You know? "And let's make cookies!" He just recognized the importance of little things you can do to make day-to-day life so much exponentially better. And he was determined to do that all the time.

TARA REESE: He appreciated leaving the light on all night so there would be a bunch of moths in morning. Or he appreciated a perennial garden, and would say, like, "Look at their perennial garden!" [laughs] You know? Or a compost pile. A perfect song being played at the perfect time.

ERICA: What did he look like?

TARA REESE: He—he wasn't very tall. He was 5'7" or—he had long—when he was little he had really long hair, like, down close to, you know, his hip bones, probably. And then as a teenager he would let it grow, you know, down past his shoulders, cut it. Let it grow long again. But then about a month before he died he cut it. That's something I think about a lot. Yeah.

ERICA: That's Tara, Finn's mother. Finn Rooney killed himself on January 3, 2020, in the afternoon after school. This story will not explain why he did this—as if anyone can explain why a person takes his own life. Suffice to say that not a single person in his life predicted this. There were no signs. The closest one can say is that there was a flash of high emotion that comes with youth, and there was a gun nearby and bullets.

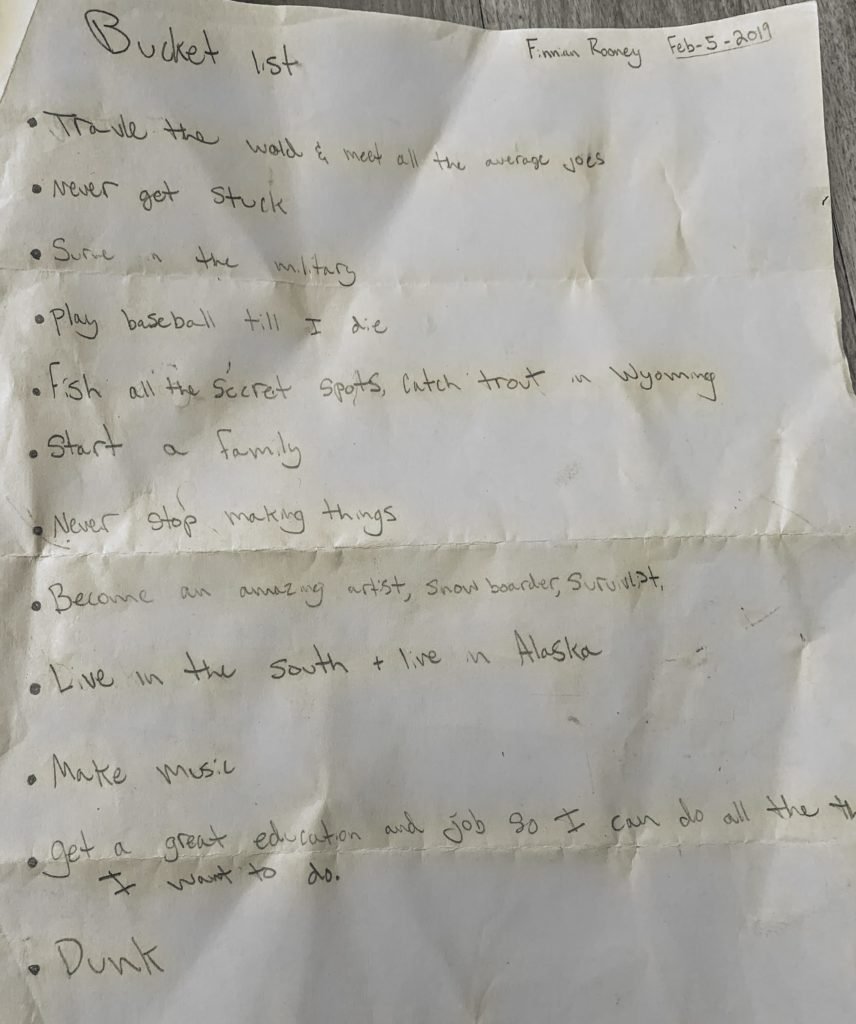

ERICA: This is not a story about suicide. It's a story about a boy called Finn Rooney who lived in Walden, Vermont near Hardwick, with his mother Tara and brother Lyle, and occasionally his father Alex, who is a long-haul truck driver. A boy who loved to fish and play baseball. He played the euphonium—not very well. He was the student body president, and right before he died, he had an idea about a bell.

ERICA: This is Finn's friend Alex talking about the town of Hardwick.

ALEX: Well, Hardwick's more like a, you know, just—they got pretty much everything to a certain extent. There's a couple grocery stores, but they ain't big by any means. There's a Walgreens, there's a couple banks, two hardware stores. Gun shop, car deal—Ford dealership. So there's not a whole lot, but that's definitely more than what Greensboro has.

ERICA: And what is the—what are the people like in Hardwick, different from Greensboro?

ALEX: Well, Greensboro they're more—I've come across from working at Willey's over here in Greensboro, that Greensboro folk are a little more high class, I guess you can call it. They have a little more—their pockets are a little deeper, and they're a little more liberal, I guess you could say. But then Hardwick, you know, it's just a bunch of hicks, a good share of them.

ALLEIGH: Hardwick's kind of like—it's the perfect combination of hippies and rednecks, hippy-redneck combination type of thing.

ERICA: This is Finn's friend Alliegh.

ALLEIGH: For lack of a better word, like a cesspool of, like, hip-necks. [laughs]

ERICA: What was Finn?

ALLEIGH: Finn was a total hip-neck. He was the most ideal combination of a hip-neck you can get. He wasn't—because sometimes there's some that are 70-30 percent hippie-redneck. Fin was 50-50. He was right in the middle. If you needed him to help you weed your garden, he'd do it. If you needed him to help fix your truck, he'd do it. It was just—he was very much in the middle. Could do anything you asked him to do.

MAC: He partook in activities of every single crowd around.

ERICA: This is Mac.

MAC: He was the star baseball player. He was the student council president. He was—he liked to go and fish and hunt and work on his truck. I mean, he did everything, and that's why he was friends with everybody.

ERICA: Again, here's Finn's mom Tara.

TARA REESE: You know, there—it's a farming community, a logging community. People lived here for six generations. There's like last names that are last names, you know? And Finn was like, "How long would it take for Rooney to be like a Hardwick last name," you know? And people were like, "200 years, maybe?" [laughs] You know? And so we were like, we've got our work cut out for us. So he was—he was active in Bread and Puppet, a theater group in Glover. As a really little kid, when we first moved here in 2010, he really wanted to do that. So he joined the band, kind of—or he would, like, play in parades and stuff that first year we came.

TARA REESE: But he was also looking for establishing himself in Hardwick. And that's a different trajectory. [laughs] And so he joined the volunteer fire department. He was a junior firefighter. When he was—I guess that would be the first year we moved here, Butch, our neighbor, was the assistant fire chief and had been in the fire department for 50 years or something. And—and offered Finn to go. We had a pager. The pager would go off in the middle of the night, and Finn would get his gear on real fast and go out in Butch's truck, and Butch would take him to these fires.

BUTCH: And he was very interested in everything.

ERICA: This is Butch.

BUTCH: He paid attention to every last thing that was going on, and he wanted to learn everything that was going on. When you're at a fire, he was right there wanting to see how everything was done, and why it was done. And that—that was him. He was just—he was 17, but his mind was, I think, way more than 17.

ARRON: I first met Finn, we went fishing.

ERICA: This is Arron.

ARRON: We had our fishing spots, and people always wanted to go with us, but it was usually just a me-and-him thing. It was really fun going trout fishing with him because he knew the rivers pretty well.

ERICA: That's as much as Arron wanted to say to me. I asked if, instead of talking, he could take me to one of their fishing spots.

ERICA: This is good.

ARRON: So this is one of me and Finn's fishing spots.

ERICA: Where are we?

ARRON: We are at one of me and Finn's fishing spots.

ERICA: You're not gonna tell me where this is.

ARRON: No. I won't tell anybody where this spot is. It's me and Finn's spot.

[Woman shouting: Ladies and gentlemen, step right up!]

ERICA: This is the sound of the Bread and Puppet Circus.

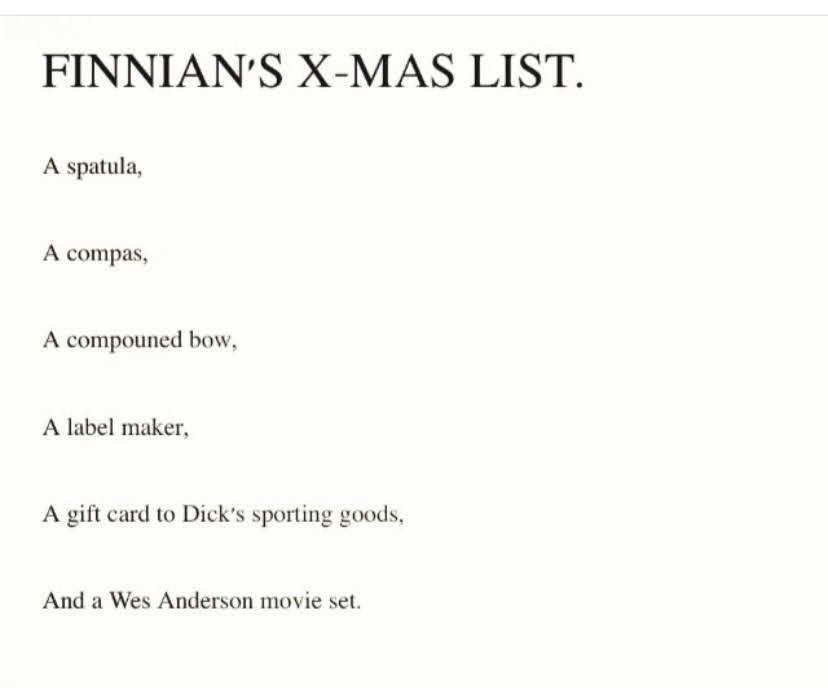

TARA REESE: He wrote poetry. Embroidered. [laughs] Drove his truck really fast. Pissed off the neighbors. Loved a good meal. Like, "This is so good, Mama!"

TARA REESE: I remember he would go out sometimes when I was making dinner, and—and pick, like, seed heads, put 'em in a Mason jar and stick it on the table. Light candles, you know, without asking. He liked a well-set table.

[MIRKO: That's it, Finn! Whoo!]

ERICA: This is Mirko, Finn's baseball coach.

MIRKO: Finn had this glove that was given to him. And during the game, the strings would break and we'd restring it. And we're like, trying to give him a glove and he's like, "Coach, this is the glove." And he had these cleats that were duct-taped up. There's a new pair of cleats that were given to him. He never had metal cleats, and at this level they can wear level. And then I seen at practice he's wearing his old duct-taped cleats up, and I'm like, "Finn, you got a new set of cleats." "Coach, those are for games only. I wear those for games." So then after every game, he'd take them off and wipe them down and put them back in the box.

MIRKO: We brought up some teams in New England, and we represented Vermont. And the coaches from the other team would come up to me and say, "Who's at center field? If I had nine players like that ..." So even coaches that never coached him could see his work ethic and his love for the game.

TARA REESE: Lyle and Finn would—every day for hours, that was the sound of summer was, like the sound of a ball getting into a glove. "Come on, Lyle! Like, let's go outside, and—" I find baseballs in the yard, you know, out in the field all the time, still. Because before we had the sheep, the grass would just get too big and they'd lose them. The balls, that sound, I'd give just about anything in the world to hear that. Yeah.

DAVID PERRIGO: It was a Friday evening, and I was at home and the phone rang.

ERICA: This is Hazen Union High School principal David Perrigo.

DAVID PERRIGO: It was our director of guidance telling me that she had some horrible news. And I said, "Okay." And she said, "We have reason to believe that one of our students took their own life this afternoon." And I shook my head and just said, "How do we know—what do you mean, 'We—we have reason to believe?' And who are we talking about?" And when she told me that we were talking about Finn Rooney, I just didn't know what to make of it. And, you know, within a couple hours, we had confirmed that it had happened, and I went to bed that night thinking I don't know what to do. I—I want to go to sleep and I want to wake up and I want this all to be gone.

DAVID PERRIGO: And I went to sleep that night and when I woke up this morning, I was like, "We've just had a terrible thing happen to our community. It's really big, and we gotta step into this and figure it out." And finally that morning, in a conversation with Finn's mom, Tara, we had to have that conversation about how we were gonna deal with this. And the community. We had to communicate to the larger community that this had happened. But from the very beginning Tara was very clear, we are not going to back away from the fact that this was a suicide. This was a suicide.

DAVID PERRIGO: And I can't tell you how helpful that was. I mean, that lifted such a burden from our shoulders about trying to pussyfoot around some kind of gentle way of breaking this to people that was gonna be half true because everybody in this community knew exactly what had happened. And I give Finn's family enormous credit. They were generous in their grief. And that was so helpful to the rest of us who were trying to figure out where do we fit here? Where do we—where do we fit in?

TARA REESE: People just rallied around us. Like a GoFundMe and a meal train and somewhere for us to stay for a couple of weeks. Boxes of, like, toilet paper and, like, tea and bourbon. So much bourbon! And, like, Lyle plays basketball, and I went to the games, which I can't believe now because I was sort of in serious shock still then. And we would sort of walk and there would almost be like a—like a sea parting, but not obnoxious. Like, I can't—I can't explain it. It was just like reverence, almost. That's not the right word. Reverence isn't the right word. It was—it was just care.

TARA REESE: They'd play the national anthem, which is obviously like a big thing for baseball, and I was like a mess, like sobbing every time they'd play the national anthem. But then whoever I was sitting by would, like, put their hand on my shoulder, and whether it was, like, a logger or, like, a mom or a—people just held us. Tom Gilbert from Black Dirt Farm set up this—this bonfire where he burned rafters from his barn, like 100-year-old very special rafters. And—and hundreds of people from town came, and there were snow machines and there were farmers on John Deeres singing hippie songs. And it was deep during the primaries, so politics were just really ugly at that time. Finn was so eager for that to be over just so people could have a bonfire. He used to say, "I just wish we could all have a bonfire." And there it was, and it was—it was really beautiful. Really transcendent and really sad.

ERICA: Finn was student body president at Hazen Union High School, and in the months before he died he heard a story about a bell, an old bell that used to hang in the belfry at Hardwick Academy in the middle of town before the school was knocked down in 1970 and Hazen Union High School was built right up the hill. He heard that they would ring this bell when Hardwick teams won away games so that the whole valley knew about the win all together.

ERICA: Finn Rooney loved this idea, which maybe isn't surprising. He was a kid who had some notion of community being something inclusive and participatory—a verb, even. He wanted to live in a town where there was a bonfire and everybody came.

TARA REESE: Finn was not a fan of smartphones or the internet in a lot of ways. So this was a way that people communicated that was different than posting it on Facebook. [laughs] And he really loved that idea. He also thought that it could bring together different people in Hardwick. The whole election stuff was really bumming him out, and he thought this was a way of—everybody would be excited to hear the bell.

TARA REESE: So he ran for student body president, and that was sort of his main platform was that he was gonna get the bell back to Hazen, and there was "Yeah!" And actually, everybody was like, "What are you—" because they didn't know about the bell. But he explained that there used to be this bell, and that he was gonna get the bell back. But that he also didn't want it just to be for sports, that he was gonna make it like if somebody won a spelling bee or if somebody was born that they would ring the bell.

TARA REESE: We talked about it a lot at dinner. His dad says he remembers Finn being in his truck and talking about the bell. Like, it was just this thing. And so then when he died, quickly there was a lot of talk about getting the bell. It sort of took on a life of its own.

DAVID PERRIGO: Finn passed away in early January, the first week of January. And his passing just rocked the community at a level that was inexplicable. No one would have ever believed that this could have happened to Finn. So when Finn passed, the community was in shock for quite a long time, and this memory, this dream that he had about the Hardwick Academy bell began to resonate with people.

ERICA: It turned out some people in town didn't want to give up the Hardwick bell, but then Dave Perrigo got a call. There was another bell lying on the bank outside the Greensboro town hall. It was the bell from the old Greensboro school, which also had closed when the schools unionized and Hazen was built. And the people of Greensboro were glad to donate it to Hazen.

KIM GREAVES: The fact that he felt strong enough that Hazen's community could use a bell that would bring the school together for all of our high points, you know, games and graduations, just to ring out, you know, I think that's a wonderful thing. And surprisingly, no one had come up with that before.

ERICA: This is Greensboro town clerk Kim Greaves.

KIM GREAVES: Like, everybody was supportive of having our bell taken care of in a way that obviously we had not done. And I mean, it's got a wicked, beautiful tone, and I think it's gonna be spectacular. As old as it is, it is an incredible tone, so it's gonna—hopefully, you know, I mean, all the games and the graduations that'll ring forever and it will be restored to its glory.

ALEX: My truck, the '83 Chevy K30. It's a single cab long bed. It's an eight-inch lift, 40-inch tires. Makes about 500 horse. Had some transmission problems recents, but hope it holds together for today's mission. Finn wanted to bring this bell to Hazen, and Finn's family asked if I wanted to haul the bell with my Chevy. I mean, it is a real sharp-looking truck, but ...

ERICA: Are you nervous?

ALEX: Yeah, I am. I don't know if my truck can hold together. I got the whole town of Hardwick and Greensboro on my shoulders, so I don't need to mess with that by any means. But if I do, if my truck does die then Finn will have definitely appreciated that.

[band playing]

ERICA: So on a rainy day in the spring, people gathered in the parking lot at the Greensboro town hall for the moving of the bell. Baseball players, Butch and the Walden Fire Department, town clerks and farmers and the Bread and Puppet Band and Alex with his enormous bright red truck.

[band playing]

DAVID PERRIGO: Thank you all very, very much for joining us on this very special occasion here today. When we began to launch this bell project, one of the things we thought of was that we might get our own bell, we might have a bell made for us special. And then when this bell appeared, we realized what a gift. Not a new bell, a young, inexperienced bell, but a bell with maturity and spirit, a bell that has rung out to the community of Greensboro throughout its history, and a bell that will become our bell in Hazen.

DAVID PERRIGO: So we're incredibly grateful to the town of Greensboro for this, so in our appreciation today, we would like to present this letter to the town of Greensboro.

[applause]

TARA REESE: Dear residents of the town of Greensboro, on behalf of our entire union, we would like to extend our deepest thanks to our friends and fellow union members of the town of Greensboro for your gracious gift of the former Greensboro school bell to Hazen and the entire union. The gift has allowed us to advance a dream first articulated by our former student body president Finn Rooney to bring a working bell back to Hazen to once again ring out over the hills and the valleys of our community, to inform, to celebrate, to unify and to heal—a theme that is a tremendous part of our beloved student's legacy. Today we plan to welcome your bell to its new life as our union's bell. [sobs]

TARA REESE: Sorry! We commit to caring for it in its new home and respecting its great history as it begins its new life and mission to once again and into perpetuity sound its golden tone across our beloved greater community.

[applause]

[band playing]

[sound of bell being lifted]

MAN: How we doing?

MAN: Gotta—gotta bring that end a little bit towards me. There you go.

MAN: If you would like to motivate and inspire this group of people with the revving of your truck ...

ALEX: [laughs]

MAN: ... that would be cool. That would get people, like, mobilized and realizing that we're good to go.

ALEX: Oh, the fire truck's already down there?

[truck revs engine]

[band playing]

ERICA: And so Alex and Lyle and a few other guys loaded the bell into the back of Alex's '83 Chevy K30, and the whole party, along with the Walden Fire Department and the Bread and Puppet Band, convoyed down to Hazen Union to deliver the bell to its next home—just like Finn wanted.

TARA REESE: It—it never felt clumsy. It was, like, so not clumsy, in a town that maybe a lot of people consider clumsy and—and sort of, you know, Hardwick. I mean, you know, there's all sorts of jokes about Hardwick. It was sort of that idea of Hardwick that was actually the most beautiful, real, human experience of my entire life. I walked to the—go to my mechanic, and he was sobbing and, like, "Can I change your oil?" [laughs] Or, like, the diner has a sandwich named after him. The one-year anniversary, there were—people made snowflakes with his name on them and taped them all around town, the bell.

TARA REESE: He came home. I was on the couch, and normally as soon as either of the boys come in, I would check in with them. You know, look at their face and ask them how their day was. And they very rarely even got up the steps without us talking for 10 minutes or something about—about their day. But this day was different. And his dad caught him at the door. We didn't—it was winter, and we needed wood for the fire, and I said, "Hey Finn, can you grab some wood for the fire?" And he said, "Yep." And he went back outside, grabbed some wood for the—for the wood stove. Was coming in through the mud room, and his—I said—or his dad said, "Hey, you wanna go out to get something to eat?" And Finn said, "Nah, I'm not hungry." And he went upstairs. His dad and his brother and I were all sitting downstairs in the living room next to the—next to the chimney. And the chimney went through Finn's bedroom. So we were probably down there for five minutes? The sound went right down the chimney, and ... it took a long time to sort of—I mean, it probably was half a second, but in my head it—it—I knew. Then we all started screaming pretty much, except Lyle. He was just standing there, and—and, "I'm just gonna go get Butch. Butch will know what to do. He's on the fire squad."

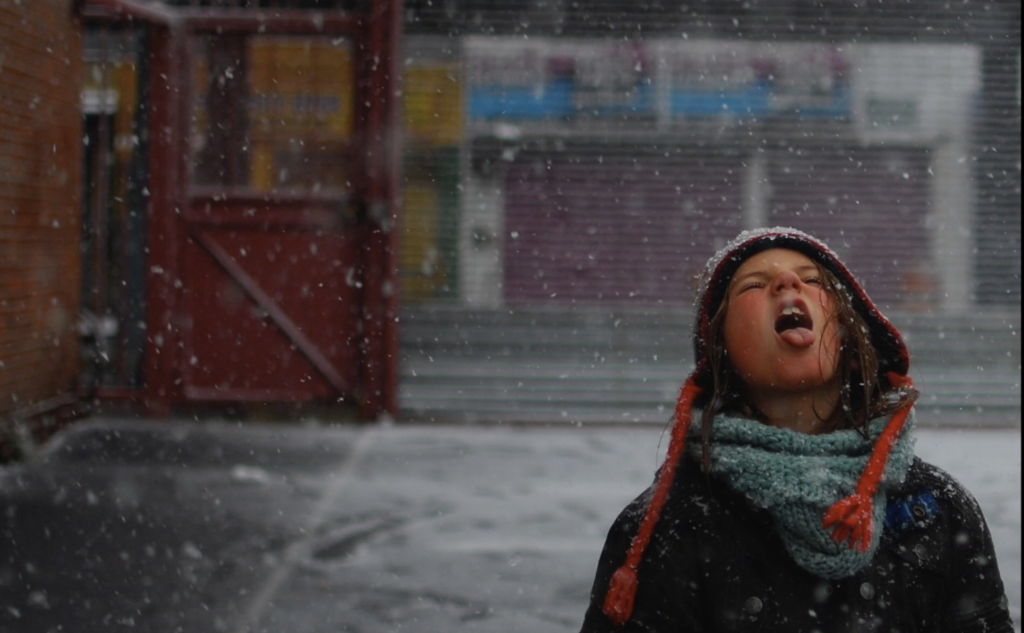

TARA REESE: And I went outside. It was snowing. It was beautiful. I put on whichever boots I could find. They were mismatched and, like, one of Finn's and one was Lyle's like Bog's. And they were both left feet. [laughs] And—and I—it was like I was watching it all. I can't—I can't explain, but—but not—it's not that I wasn't present. I was, like, fully present but also, like, watching it at the same time. I don't know if that makes any sense, but I—I got to the barn. They have this big floodlight on their house. I got there and it was snowing. And you know sometimes when you look up at a light and it's snowing it's like so beautiful. And I stopped screaming—I'd been screaming this whole way. And I looked up at that light. It was snowing, and it felt like there was no time, like at all.

TARA REESE: Like, and the whole life flashing before your eyes thing, I guess there was a part of that because I could see Finn at all of his ages all at once. All at once. And me all at once and, like, everybody I'd ever met all at once. I mean, it sounds so—but, like, you know, volcanoes and, like, dinosaurs and the Big Bang. Seasons, like, rapidly changing, you know? Like, me getting old without him. Him being old. Like ... [cries]

TARA REESE: It kind of was like me saving God. I'd say that's the best way I've ever described it. And I—I felt Finn was, like, gathering, like, all of what was left of him. Like, the energy that was still, like, all, like, everywhere because he was just such a big person. And—and I was like sort of waiting kind of patiently almost for it to all, like, gather. And then it was like, "Zzzz." Like, it just sort of got in me somehow is how I felt it. You know, I've explained this, like, very few times, but it was like infinite compassion for, like, every single person that had ever lived, like including me and including Finn for doing this.

TARA REESE: I remember saying out loud, "Oh!" Like, I understood for—for just a second there, like, why we were alive. And it felt like it was for each other.

[bell ringing]

-30-